The Himalaya Project

Back to the writing desk, I penned a letter to the Queens Harbourmaster, Portland Naval Base. The reply was discouraging: “I have made local enquiries regarding the wreck of the Himalaya. You are right in saying that the wreck on the inside of the breakwater is not the Himalaya, and I am grateful to you for ascertaining that it is probably the Countess of Erne. Himalaya was demolished by explosives at some time after the war. The pieces were cut up and landed at Castle town Pier for scrap.”

Well, having come this far, I was determined come hell or high water I was going to find some remains of the Himalaya, even if it was only a rivet, after all, she was once the largest ship in the world. If she had lain with her masts above water for any time, she must have been charted.

Letter to the Hydrographer: “In exchange for information on the Countess of Erne, how about a copy of a chart of Portland for the period, say, end of 1941 to 1945?”

I was overwhelmed by the generosity of the response. Free of charge I was sent copies of charts for 1934, 1945, 1946, a large scale chart for 1945, and a new metric chart. Low and behold, there she was, clearly marked and on the 1934 chart, a coal hulk was marked over the same position!

Transposing the position on to the new chart was simple, as was finding some good transits. lt gave a position about half a mile south of where we had planned our search.

On Monday, 31st March 1975, after a bitterly cold Easter during which three quarters of our party had returned home, seven of us set out in the fibre-glass boat owned jointly by Mick Phipps, Eric Bargent and Max Goodey.

Diving that day were Barry Winters, Max Goodey, Pat Maroney, Graham Rackley, Tony Raven, Geoff Hughes and myself. We sailed out along one transit until we closed the other. The echo sounder was switched on and immediately we picked up a scattered echo. Tony and Geoff were first down. Two minutes later they were back up: “There’s plates and wreck-age everywhere!!”

I dived with Graham. At 40ft we entered a cloud of stirred silt, headed north and after a few fin strokes found ourselves hovering over a plain of grey ooze from which protruded a tangle of unrecognisable metal. We took a closer look. lt was immediately obvious that what we were looking at was the remains of an old ship that had been blown up. The plates were iron and not steel, riveted and not welded. They were badly distorted. We explored further. Odd lengths of pipe a lot of waterlogged wood-that struck a chord.

Letter from Mr. W.C. Cook: “In the days following the bombing, the wind was easterly and a considerable quantity of wreckage was washed ashore. This timber was teak, and I collected some of this from which later I was able to make various articles …”

We came across many pulley blocks–part of the Temperley gear? Getting low on air we decided to bring a couple up–still bound together with tarred rope. The sheaves, when stripped apart, were found to be thick with coal dust. We had only explored a relatively small amount of wreckage – how much more lay round about? After everyone else had dived, Graham and I decided to go for an anchor ride. Grabbing a fluke each, Max guided the boat over quite a large area. We were down to 30 ats apiece before we came across any more extensive wreckage – no time for more than a brief look before it became imperative to surface. Max had taken some marks; we would return.

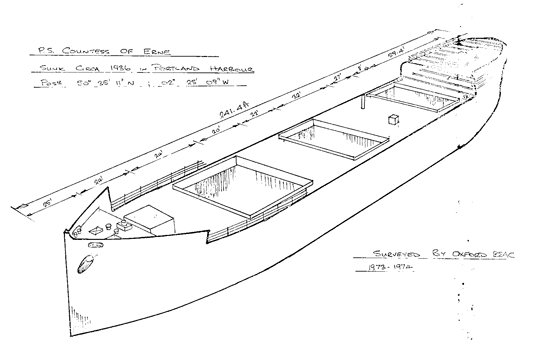

Countess of Erne sketch

Countess of Erne sketch